Source: Atlas Public Policy.

Atlas just released a study on the medium and heavy duty electric vehicle charging needed to get to full electrification. Electric trucks really matter: Almost 30 percent of ground transportation greenhouse gas emissions come from medium- and heavy-duty (MDHD) trucks, and they spew harmful air pollutants – often into low-income communities and communities of color.

Heavy-duty tractor-trailers are particularly high polluters due to their low fuel economy and the long distances they travel. These vehicles – think those trucks where you start to sweat as they approach in the rearview mirror – represent only 13 percent of on-road MDHD vehicles but generate approximately 60% of their greenhouse gas emissions.

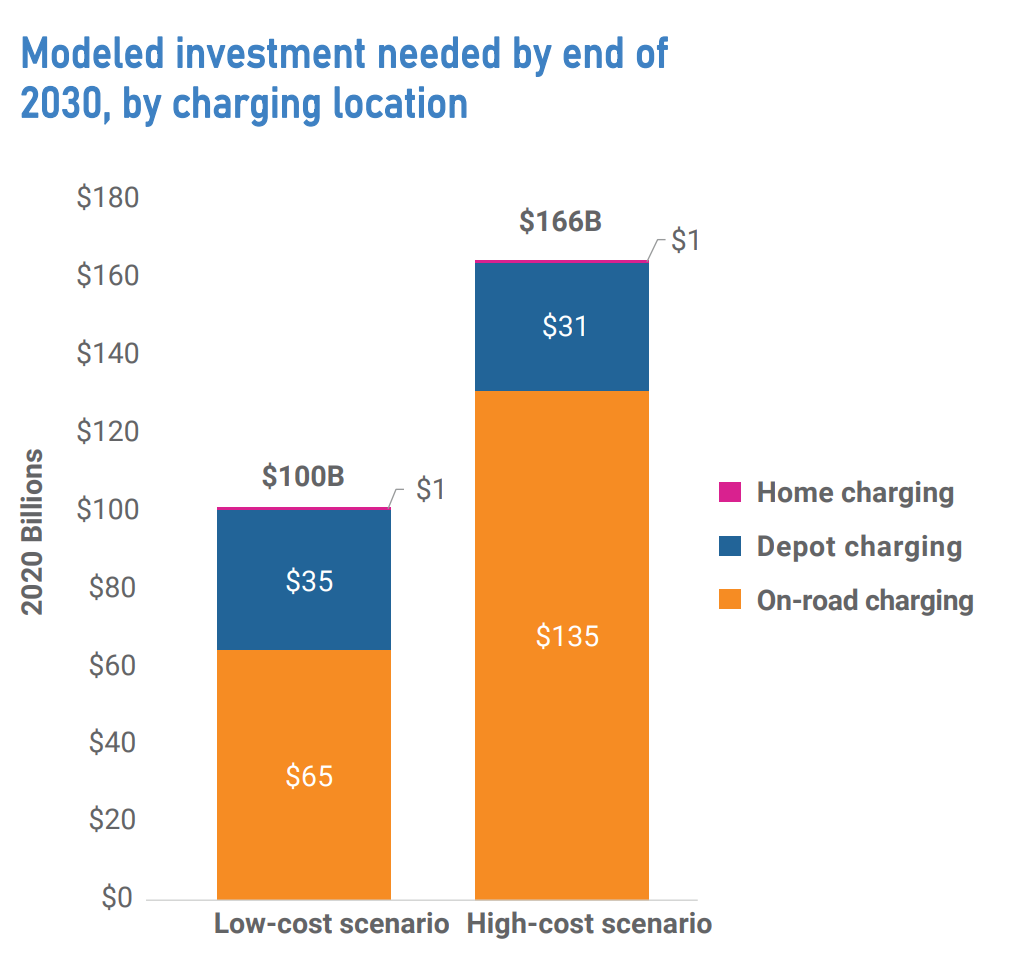

Our study found that between $100 and $166 billion in charging infrastructure investments will be needed this decade in order to reach 100 percent electric MDHD truck sales in the United States by the end of 2040. This reflects installed charging infrastructure costs not expected to be covered by electric utilities (and excluding siting, contracting, and any on-site solar or battery storage). We found a need for a significant ramp-up in charging of all kinds, including at-home charging for pickups; depot charging for fleets; and a variety of on-road charging options, including some ultra-high-powered stations for long-haul trucks.

Importantly, we did not model the many benefits to truck electrification: financial benefits; reductions in greenhouse gases, noise and air pollution; and improved health outcomes. These have been shown elsewhere to be substantial. In particular, work by others has shown that electric depot-charging trucks will be cost-competitive with diesel in the near future on a total cost of ownership basis, including charging. We also assume that battery electric truck technologies will continue to improve, enabling industry to expand beyond the many electrification opportunities that already exist to all use cases.

A $66 billion window is quite something so let me explain. The many charging solutions we modeled fit into four broad categories:

· at-home charging for large pickups (a very small part of the pie);

· depot charging for fleets;

· on road charging for long haul tucks; and

· on road charging for other trucks.

The main reason for the cost differential is that we modeled two different levels of utilization for on-road charging (in plain English: how much does each charger get used in a day?) The more vehicles that use a single charging station, the fewer stations (and thus less investment) are needed to recharge vehicles.

Less important but still significant was the amount of on-road versus depot charging done by fleet vehicles. Long-haul trucks are always assumed in our analysis to charge on-road at truck stops or other parking spaces. But for other fleet vehicles we assume in the low-cost scenario that 90% of charging is done at a depot overnight and 10% is done on-road. In the high-cost scenario, we assume it is 75% and 25%.

The last factor to explain the range in estimates is variation in how much of the cost will be paid for by utilities. In many cases, charging station deployment will require grid upgrades. The cost of deploying stations to non-utility players will depend on how much of those upgrade costs are covered by utilities across the country.

The research points to three key principles that can increase utilization and therefore control costs for on road charging. First, target charging first to high-traffic, complete routes that can kickstart early adoption. Next, plan charging that can accommodate several vehicle types, and last, deploy technology to allow drivers to reserve electrified parking spaces to use charging as efficiently as possible.

Planning ahead will also be key to keeping costs down. MDHD charging may take long lead times to plan, permit and build, and the high power needs of long-haul trucks will likely require utility upgrades with longer timelines. This means that early investment commitments are crucial to ensure that we are ready for an electric truck future.

To state the obvious, at least $100 billion in committed investments this decade is a lot. But these investments will unlock the substantial cost savings from electrifying trucks. Cost savings do not just stem from cheaper-to-operate trucks and lower expected maintenance costs, but also from significantly reduced costs from climate change, and lower rates of asthma, cancer, cardiovascular disease, and premature death. These savings will be most impactful for low income communities of color that have historically faced the brunt of harms from these vehicles.